Turns out I am anxiously attached…so now what?!

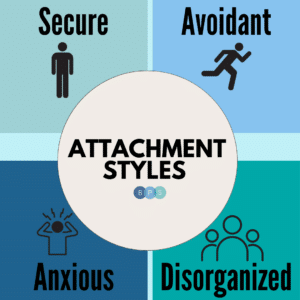

Thank you, readers, for patiently waiting! Now that we have learned about what the heck Attachment Style is, we can apply some DBT tools that can help assist us in owning our attachment in a way that maintains our self-respect, our relationships, and our needs!

Imagine…you have been on three dates with someone you met on the apps. It has been going super well…or so you thought. That is, until they left you on read for two days and now you are spinning…

What did I do wrong?

Not again… I am destined to be alone.

Why does this always happen to me?

I knew it was too good to be true.

I simply can’t tolerate it until I figure out what they are thinking!

Before you say or do something you might regret, let’s slow it all down and lean on our DBT skills with the steps laid out below:

Step 1: Check SUDS

Check your emotional temperature. SUDS stands for our Subjective Unit of Distress Scale. Think about asking yourself where you fall on a scale of 0-10, where 0 symbolizes pure serenity and 10 symbolizes the most distressed you can imagine feeling. If you are lower than a 6 AND you trust that you will not act in emotion mind, (hot headed, urgent, impulsive) then skip to step 3. Otherwise, continue to step 2.

SUDS are a 9.

Step 2: Tolerate distress

Take a beat. Before saying or doing the thing that will likely damage the relationship or your self-respect and most likely not get you any closer to your objective, try the STOP skill or one of your other DBT crisis survival skills: Distract with ACCEPTS, TIP, Pros/Cons, or Self-soothe. Set a timer for 20-minutes as you one-mindfully use your Distress Tolerance skills and allow your emotional temperature to reduce to a comfortable number. You may not feel “good,” but we are aiming for “slightly better.”

I put my phone down, take a 10-minute cold shower (TIP) to calm my nervous system, I set a timer for 20-minutes and one-mindfully watch an episode of Never Have I Ever (Distract) until I feel my emotional temperature simmer down.

Step 3: Mindfulness of internal experience

Now that your SUDS are tolerable and things feel a little less dire, try to label your emotions, body sensations, urges, and thoughts. Become a curious observer of your internal world.

My SUDS are a 4. I am feeling fear. I have a tightness in my chest and jitteriness in my limbs but it is not as bad as before. I have urges to reach out and I also have urges to ruminate about the unknown. My thoughts are telling me “this is over” and “I will never find love.” I am noticing that my anxious attachment is activated right now because I am feeling afraid of abandonment in the presence of disconnection and uncertainty.

Step 4: Identify your goals

Identify what your goals are (more specifically, your long-term goals). Sometimes your goals might compete with one another, and we must choose to prioritize one or two over the other at any given point in time. What is your self-respect goal, your objective/need goal, and your relationship goal?

Because I do not know this dating prospect well, my relationship goal is to continue seeing this person and continue to be in their good graces. I don’t want to blow it before giving it a real chance! My self-respect goal is to correspond with this person and also to regulate my emotions in a way that I can feel proud of. My objective/need is to connect with this person. I recognize that relieving my anxiety in the moment is a short-term objective whereas upholding my self-respect is a long-term objective.

Step 5: Act in Wise Mind

The penultimate step is to act from a place of wise mind. Wise mind could tell you something very different depending on who you are and what the context it. Your wise mind is your intuition and your inner knowing. We’ve all got one. It is a state of mind that guides you towards the life you want to be living.

Wise Mind tells me that for now, I want to prioritize my self-respect and my long-term objectives, which means tending to my emotional experience, without projecting my fears onto this person. While it would feel good in the moment to try to connect and double or even triple text (think protest behavior), I know it will compromise my long-term objectives. Wise mind tells me that it would be advantageous to soothe myself and validate my fears, focusing on connecting with well-established and safe relationships in my life. I may decide to voice my needs for more frequent communication in the future AND my wise mind tells me that it does not feel appropriate to the relationship right now. I will choose to accept the uncertainty in this moment.

Step 6: DEARMAN

If the context calls for it, you may lean on your effective communication strategies, such as DEARMAN, to accurately and effectively communicate your needs to someone else. Your aim is to accurately communicate your feelings and your needs in a way that is clear and fair, both to you, and the other person.

Instead of communicating to the person I have been on three dates with, I called my friend and let her know how painful it is to feel attachment wounds early on in dating. She was able to validate my experience and I was able to feel connected to my friend.

For more information on this topic, you can tune into our back-to-back episodes on our podcast, House on Fire.

References:

Mundin, Dr. Joann, and Katarina Schultz. DBT Self Help, 8 June 2023, dbtselfhelp.com/.